• GORNJI GRAD (UPPER TOWN) – A SHORT HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The area of today’s Zagreb has been inhabited even before the times of the Romans, whose reign here lasted until the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Nevertheless, the first document mentioning Zagreb, the Felician’s Decree, specifies 1094 as the year of founding the diocese in the already existing settlement. The settlement was located on the Kaptol hill, where the cathedral is still situated today. Kaptol is the oldest continually inhabited part of the city, and its square is the oldest square in Zagreb.

The crucial event for Zagreb’s further development is the Tatar invasion, which took place during the reign of the Hungarian king Béla IV. Avoiding the conquerors’ attack, the defeated king sought refuge and spent a short period hiding in Zagreb, escaping for the coast afterwards. In search of the king they would never catch, the Tatars sacked Kaptol, which was not sufficiently fortified for serious resistance, and set it on fire. The town’s vulnerability was the precise impulse for building a new town on the neighboring hill – Gradec or Grič.

Following the death of their ruler, the retreat of the Tatars stabilized the situation, and in 1242 Bela IV gave Gradec the Golden Bull, the privilege of a free sovereign town, which brought new status to the town and ensured its development.

Although a part of the population moved to the Gradec hill upon building the new town, the Kaptol part of Zagreb remained in existence. It was only in 1850, after numerous conflicts, that the two towns united, forming the city of Zagreb.

The battles between the neighboring settlements, the diocesan Kaptol and the free and sovereign Gradec, were fought for land, mills or political reasons. The most famous among them took place near the bridge connecting the two banks of the Medveščak stream, which still flows underground between the two hills. The bridge was later named Krvavi most (Bloody bridge), and today Krvavi Most Street stands in its place.

Although the name Zagreb was used already in the Felician’s Decree, the name was occasionally used for both Gradec and Kaptol, and from the 16th century on its use for both municipalities became more frequent.

In 1577 the Parliament of the kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia assembled, concerned about the threat of a Turkish invasion, and recommended king Ferdinand to „take care of his royal town on Gradec hill, the capital of this region“. This was the first mention of Zagreb as the Croatian capital. Varaždin will later take up the primacy for a short period of time.

The court of the Croatian governors was not in Zagreb until the 17th century. The first one to choose Gradec for his court was Nikola Frankopan in 1621.The precise location of the royal court on the Gradec hill is unknown today, but it was probably situated on its western part, near St. Mark’s Square.

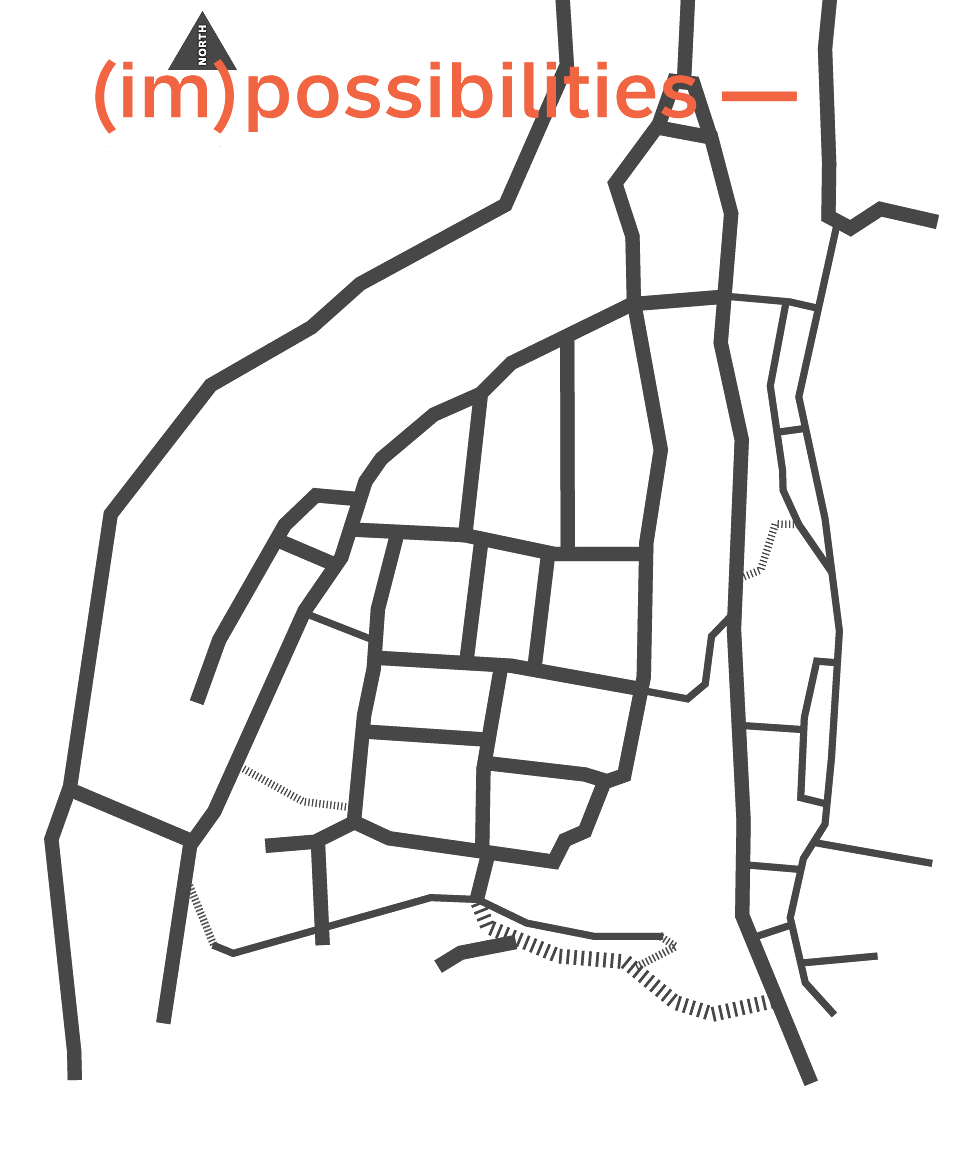

Gradec attained its urban shape when the ramparts were built in mid-13th century, and in its basis the shape is preserved today. Walls with towers and gates formed a triangle surrounding the town on the top of the hill, which determined the town’s parameters. Zagreb’s expansion towards Zagreb Field, i.e. the Sava river plain, determined some changes within Gradec. Some of the city gates were torn down, and in the place of the southern ramparts the first promenade with a music pavilion was built with the citizens’ donation. The plans to build a promenade that would enclose the entire Upper Town were never carried out, and in some places the former ramparts were replaced by parks (Grič Park) and courtyards (Jelačić palace in Demetrova street).The original wooden architecture was replaced by brick-wall buildings due to frequent fires. Apart from the ramparts and St Mark’s Church, which stems from the town’s earliest period (it was redesigned in the 19th century), the oldest buildings still existing in Zagreb are two 18th century low-rises in Matoš Street.

The name Gornji grad appeared in the early 19th century because of the rapid growth of the lower town, which by the end of the century became the center of the modern city. The historical development of Gornji grad is reflected in its street nomenclature. For example, there used to be a Beer Street named after a brewery.

Since the foundation of Gradec, the centre of the town has been St Mark’s Square. It was named after the church supposedly built by Venetian masters, after which one of the nearby streets was named. The church was almost torn down in the late 19th century, but because of the lack of money to build a new church, it was renovated after all, getting its characteristic roof with coats of arms.

Given that St Mark’s Square was the main town square, the two century old governor’s palace was built there, and in 1907, on the opposite side of the square, the parliament building was erected. That was the first case in Zagreb that applications for a building project were invited publically. The fact that the space was politically conditioned influenced the building of the underground tunnels beneath Gornji grad, used as shelter or a potential escape route for the fascist leadership during WWII.

However, throughout the centuries St Mark’s Square was primarily recognizable for St Mark’s Fair, which stems from 1256. On the square in front of the church stood the pillory to which convicts were tied. Upon its removal, a monument to Virgin Mary was erected, but because of its bad condition, it was taken down in the 19th century.

According to a legend, Matija Gubec, the leader of the Peasant’s Revolt, was crowned with a red-hot iron crown on the Square in 1573. He wasn’t executed there, but in a place called Zvezdišče, the woods on the western side of Gradec (the threshold of the Tuškanac forest). Zvezdišče is also the place of Zagreb’s femicide, since for centuries it was the place where women accused of witchcraft were burned at the stake.

St Mark’s Square is also the place where at Easter 1794, after an anonymous night-time action which stirred the entire town, a tree of freedom appeared, topped with a Jacobin hat, and decorated with forty stanzas of a revolutionary poem in Croatian, which was still not the official language.

A massacre took place on the square in 1845, during a protest against the Magyarization of the country. A large number of people were wounded, and fifteen died – nowadays they are known as the July victims.

At the beginning and the end of the 20th century the Square was the scene of prevailingly unsuccessful political assassinations. Today every kind of public protest is antidemocratically forbidden on St Mark’s Square, which serves merely as a stage for presidential inaugurations.

Gornji grad remained the most complete part of old Zagreb, and its historical space is greatly present in the political and artistic consciousness, not only in Zagreb, but in the whole of Croatia. The medieval atmosphere of Gornji grad described by August Šenoa in his novel Zlatarevo zlato (The Goldsmith’s Gold) remains the ideal image of Zagreb. The monument to young Dora, one of the main characters in the novel, exists today next to Kamenita vrata (Stone Gate), one of the remaining towers and gateways to the old center of the capital, which is „by its proportions and qualities so characteristic for the history of this country“.

Saša Šimpraga, historian